Canada In The Cold War on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Canada in the Cold War was one of the

To defend

To defend

During the

During the

Canada also maintained diplomatic and economic ties with Cuba following the

Canada also maintained diplomatic and economic ties with Cuba following the

In 1987, Canada released a long-awaited

In 1987, Canada released a long-awaited

The Cold War in Canada came to an end during the period of 1990–1995 as the traditional mission to contain Soviet expansion faded into the new realities of warfare. The Cold War required permanent foreign deployments to Western Europe, something which was no longer necessary, and as such bases closed down. Less equipment was needed, and so much was sold off, soon to be replaced by newer equipment designed for future conflicts. At home, bases were closed and operations consolidated and streamlined for maximum efficiency, as by the early 1990s many Canadians were openly questioning the necessity of large defence budgets.

In 1990, Canadian troops were deployed to assist provincial police in Québec in an effort to defuse tensions between Mohawk Warriors and the

The Cold War in Canada came to an end during the period of 1990–1995 as the traditional mission to contain Soviet expansion faded into the new realities of warfare. The Cold War required permanent foreign deployments to Western Europe, something which was no longer necessary, and as such bases closed down. Less equipment was needed, and so much was sold off, soon to be replaced by newer equipment designed for future conflicts. At home, bases were closed and operations consolidated and streamlined for maximum efficiency, as by the early 1990s many Canadians were openly questioning the necessity of large defence budgets.

In 1990, Canadian troops were deployed to assist provincial police in Québec in an effort to defuse tensions between Mohawk Warriors and the

Cold War Canada, 1945-1991

" Ch. 9 in ''Canadian History: Post-Confederation''. BC Open Textbook Project. *Cavell, Richard, ed. 2004. ''Love, Hate, and Fear in Canada's Cold War''. University of Toronto Press. 216 pp. * Adam Chapnick. 2005. ''The Middle Power Project: Canada and the Founding of the United Nations'' University of British Columbia Press. . * Clark-Jones, Melissa. 1987. ''A Staple State: Canadian Industrial Resources in Cold War.'' U. of Toronto Press. 260 pp. * Clearwater, John. 1998.

Canadian nuclear weapons: the untold story of Canada's Cold War arsenal

'. Dundurn Press. * Cuff, R. D. and J. L. Granatstein. 1975. ''Canadian-American Relations in Wartime: From the Great War to the Cold War.'' Toronto: Hakkert. 205 pp. * David, Dewitt, and John Kirton. 1983. ''Canada as a Principal Power.'' Toronto: John Wiley. * Donaghy, Greg, ed. 1998. ''Canada and the Early Cold War, 1943–1957.'' Ottawa: Dept. of Foreign Affairs and International Trade. 255 pp. * Eayrs, James. 1972. ''In Defence of Canada. III: Peacemaking and Deterrence.'' U. of Toronto Press. 448 pp. * Granatstein, J. L., and David Stafford. 1991. ''Spy Wars: Espionage and Canada from Gouzenko to Glasnost''. . * Herd, Alex. 2006 February 6.

Canada and the Cold War

" ''The Canadian Encyclopedia'' (last edited 2021 March 6). *Holmes, John W. 1979, 1982. ''The Shaping of Peace: Canada and the Search for World Order, 1943–1957,'' 2 vols. University of Toronto Press. * Hristov, Alen. 2018 December 8.

The Gouzenko Affair and the Development of Canadian Intelligence

" ''

It's War. It's War. It's Russia

" ''

Canada and NATO

" Dispatches: Backgrounders in Canadian Military History. ''

The DEW Line

" '' The Beaver'' (Winter 1983):14-19. *Tucker Michael. 1980. ''Canadian Foreign Policy: Contemporary Issues and Themes.''

Cold War Culture: The Nuclear Fear of the 1950s and 1960s

" ''CBC Digital Archives''.

– '' Canada: A People's History'', CBC Learning

Project Rustic: Journey to the Diefenbunker

– Diefenbunker Canada’s Cold War Museum, Canadian Heritage

Archived

*"Gouzenko: The Series" (podcast) – ''

Gouzenko Deciphered

(2020 September 8), interview with Evy Wilson, daughter of Igor Gouzenko *

Gouzenko Deciphered Part 2

(2020 October 7), interview with Calder Walton *

Gouzenko Deciphered Part 3

(2020 October 21), interview with Andrew Kavchak

Cold War Tech and Its Discontents

(2021 January 26) – ''Canada's History'', Canada's National History Society {{DEFAULTSORT:Canada in the Cold War

western powers

The Western world, also known as the West, primarily refers to the various nations and states in the regions of Europe, North America, and Oceania.

playing a central role in the major alliances. It was an ally of the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

, but there were several foreign policy differences between the two countries over the course of the Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because t ...

.

Canada was a founding member of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO, ; french: Organisation du traité de l'Atlantique nord, ), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental military alliance between 30 member states – 28 European and two No ...

(NATO) in 1949, the North American Aerospace Defence Command (NORAD) in 1958, and played a leading role in United Nations peacekeeping operations

The Department of Peace Operations (DPO) (French: ''Département des opérations de maintien de la paix'') is a department of the United Nations charged with the planning, preparation, management and direction of United Nations peacekeeping, UN ...

—from the Korean War

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Korean War

, partof = the Cold War and the Korean conflict

, image = Korean War Montage 2.png

, image_size = 300px

, caption = Clockwise from top:{ ...

to the creation of a permanent UN peacekeeping force during the Suez Crisis

The Suez Crisis, or the Second Arab–Israeli war, also called the Tripartite Aggression ( ar, العدوان الثلاثي, Al-ʿUdwān aṯ-Ṯulāṯiyy) in the Arab world and the Sinai War in Israel,Also known as the Suez War or 1956 Wa ...

in 1956. Subsequent peacekeeping interventions occurred in the Congo (1960), Cyprus

Cyprus ; tr, Kıbrıs (), officially the Republic of Cyprus,, , lit: Republic of Cyprus is an island country located south of the Anatolian Peninsula in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Its continental position is disputed; while it is ...

(1964), the Sinai (1973), Vietnam

Vietnam or Viet Nam ( vi, Việt Nam, ), officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam,., group="n" is a country in Southeast Asia, at the eastern edge of mainland Southeast Asia, with an area of and population of 96 million, making ...

(with the International Control Commission

The International Control Commission (ICC), or in French la Commission Internationale de Contrôle (CIC), was an international force established in 1954. More formally called the International Commission for Supervision and Control, the organisati ...

), Golan Heights

The Golan Heights ( ar, هَضْبَةُ الْجَوْلَانِ, Haḍbatu l-Jawlān or ; he, רמת הגולן, ), or simply the Golan, is a region in the Levant spanning about . The region defined as the Golan Heights differs between di ...

, Lebanon

Lebanon ( , ar, لُبْنَان, translit=lubnān, ), officially the Republic of Lebanon () or the Lebanese Republic, is a country in Western Asia. It is located between Syria to the north and east and Israel to the south, while Cyprus lie ...

(1978), and Namibia

Namibia (, ), officially the Republic of Namibia, is a country in Southern Africa. Its western border is the Atlantic Ocean. It shares land borders with Zambia and Angola to the north, Botswana to the east and South Africa to the south and ea ...

(1989–1990).

Canada did not follow the American lead in all Cold War actions, sometimes resulting in tensions between the two countries. For instance, Canada refused to join the Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (also known by #Names, other names) was a conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. It was the second of the Indochina Wars and was officially fought between North Vie ...

; in 1984, the last nuclear weapons

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions ( thermonuclear bomb), producing a nuclear explosion. Both bom ...

based in Canada were removed; diplomatic relations were maintained with Cuba; and the Canadian government recognized the People's Republic of China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, most populous country, with a Population of China, population exceeding 1.4 billion, slig ...

before the United States.

The Canadian military maintained a standing presence in Western Europe

Western Europe is the western region of Europe. The region's countries and territories vary depending on context.

The concept of "the West" appeared in Europe in juxtaposition to "the East" and originally applied to the ancient Mediterranean ...

as part of its NATO deployment at several bases in Germany—including long tenures at CFB Baden-Soellingen CFB may refer to:

* College football

*Canadian Forces base, military installation of the Canadian forces

* Caminho de Ferro de Benguela, railway in Angola

* Carrollton-Farmers Branch Independent School District

*Cipher feedback, a block cipher mode ...

and CFB Lahr

Canadian Forces Base Lahr (IATA:LHA, ICAO: EDTL, former code EDAN) was a military operated commercial airport located in Lahr, Germany. It was operated primarily as a French air force base, and later as a Canadian army base, beginning in the l ...

, in the Black Forest

The Black Forest (german: Schwarzwald ) is a large forested mountain range in the state of Baden-Württemberg in southwest Germany, bounded by the Rhine Valley to the west and south and close to the borders with France and Switzerland. It is ...

region of West Germany

West Germany is the colloquial term used to indicate the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG; german: Bundesrepublik Deutschland , BRD) between its formation on 23 May 1949 and the German reunification through the accession of East Germany on 3 ...

. Also, Canadian military facilities were maintained in Bermuda

)

, anthem = "God Save the King"

, song_type = National song

, song = "Hail to Bermuda"

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, mapsize2 =

, map_caption2 =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name =

, es ...

, France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

, and the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and ...

. From the early 1960s until the 1980s, Canada maintained weapon platforms armed with nuclear weapons

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions ( thermonuclear bomb), producing a nuclear explosion. Both bom ...

—including nuclear-tipped air-to-air rockets Air-to-air can refer to:

* Air-to-air combat

* Air-to-air missile

* Air-to-air photography

* Air-to-air refueling

* Air-to-air rocket

* Air-to-air refrigeration

See also

* anti-aircraft and 'anti-air' (adj.)

*

* Air (disambiguation)

Air is the ...

, surface-to-air missiles

A surface-to-air missile (SAM), also known as a ground-to-air missile (GTAM) or surface-to-air guided weapon (SAGW), is a missile designed to be launched from the ground to destroy aircraft or other missiles. It is one type of anti-aircraft sys ...

, and high-yield gravity bombs principally deployed in the Western European theatre of operations as well as in Canada.

Background

Canada emerged from theSecond World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposi ...

as a world power

A great power is a sovereign state that is recognized as having the ability and expertise to exert its influence on a global scale. Great powers characteristically possess military and economic strength, as well as diplomatic and soft power inf ...

, radically transforming a principally agricultural

Agriculture or farming is the practice of cultivating plants and livestock. Agriculture was the key development in the rise of sedentary human civilization, whereby farming of domesticated species created food surpluses that enabled peopl ...

and rural dominion

The term ''Dominion'' is used to refer to one of several self-governing nations of the British Empire.

"Dominion status" was first accorded to Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Newfoundland, South Africa, and the Irish Free State at the 1926 ...

of a dying empire

An empire is a "political unit" made up of several territories and peoples, "usually created by conquest, and divided between a dominant center and subordinate peripheries". The center of the empire (sometimes referred to as the metropole) ex ...

into a truly sovereign nation

A nation state is a political unit where the state and nation are congruent. It is a more precise concept than "country", since a country does not need to have a predominant ethnic group.

A nation, in the sense of a common ethnicity, may inc ...

, with a market economy

A market economy is an economic system in which the decisions regarding investment, production and distribution to the consumers are guided by the price signals created by the forces of supply and demand, where all suppliers and consumers ...

focused on a combination of resource extraction

Extractivism is the process of extracting natural resources from the Earth to sell on the world market. It exists in an economy that depends primarily on the extraction or removal of natural resources that are considered valuable for exportation w ...

and refinement, heavy manufacturing, and high-technology research and development. As a consequence of supplying so much of the war effort for six long years, Canada's military grew to an exceptional size: over a million service personnel, the world's fifth largest surface fleet and fourth largest air force

An air force – in the broadest sense – is the national military branch that primarily conducts aerial warfare. More specifically, it is the branch of a nation's armed services that is responsible for aerial warfare as distinct from an ...

. Despite a draw-down at the end of the war, the Canadian military nonetheless executed Operation Muskox

Operation Musk Ox was an 81-day military exercise organized by the Canadian Army in 1946. It involved the 48 members of the Army driving 11 4½-ton Canadian-designed snowmobiles ("Penguins"). They were joined by three American observers in a smalle ...

, a massive deployment across the Canadian Arctic designed in part to train for a ground and air war in the region. Canadians also assisted in humanitarian efforts, and sent observers for the United Nations to India and Palestine in 1947 and 1948.

There was never any doubt early on as to which side Canada was on in the Cold War due to its location and historical alliances. On the domestic front, the Canadian state

State may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Literature

* ''State Magazine'', a monthly magazine published by the U.S. Department of State

* ''The State'' (newspaper), a daily newspaper in Columbia, South Carolina, United States

* ''Our S ...

at all levels fought vehemently against what it characterized as communist subversion. Canadian and business leaders opposed the advance of the labour movement

The labour movement or labor movement consists of two main wings: the trade union movement (British English) or labor union movement (American English) on the one hand, and the political labour movement on the other.

* The trade union movement ...

on the grounds that it was a Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

conspiracy during the interwar period

In the history of the 20th century, the interwar period lasted from 11 November 1918 to 1 September 1939 (20 years, 9 months, 21 days), the end of the First World War to the beginning of the Second World War. The interwar period was relative ...

. The peak moments of this effort were the Winnipeg General Strike of 1919 and the anticommunist

Anti-communism is political and ideological opposition to communism. Organized anti-communism developed after the 1917 October Revolution in the Russian Empire, and it reached global dimensions during the Cold War, when the United States and the ...

campaigns of the depression, including the stopping of the On-to-Ottawa Trek.

Early Cold War (1946–1960)

In February 1946, the Canadian government disclosed to the public the defection of a Soviet cipher clerk,Igor Gouzenko

Igor Sergeyevich Gouzenko (russian: Игорь Сергеевич Гузенко ; January 26, 1919 – June 25, 1982) was a cipher clerk for the Soviet embassy to Canada in Ottawa, Ontario, and a lieutenant of the GRU (Main Intelligence Direct ...

, in Ottawa; who also disclosed the existence of a Soviet spy ring in the country. The event has been used by historians to mark the beginning of the Cold War era in Canada, with the Gouzenko Affair

The Gouzenko Affair was the name given to events in Canada surrounding the defection of Igor Gouzenko from the Soviet Union in 1945 and his subsequent allegations regarding the existence of a Soviet spy ring of Canadian Communists. Gouzenko's d ...

triggering another red scare

A Red Scare is the promotion of a widespread fear of a potential rise of communism, anarchism or other leftist ideologies by a society or state. The term is most often used to refer to two periods in the history of the United States which ar ...

in Canada.

Canada was a founding member of NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO, ; french: Organisation du traité de l'Atlantique nord, ), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental military alliance between 30 member states – 28 European and two N ...

(North Atlantic Treaty Organization), of which Prime Minister Louis St. Laurent was a chief architect. Canada was one of its most ardent supporters and pushed (largely unsuccessfully) to have it become an economic and cultural organization in addition to a military alliance.

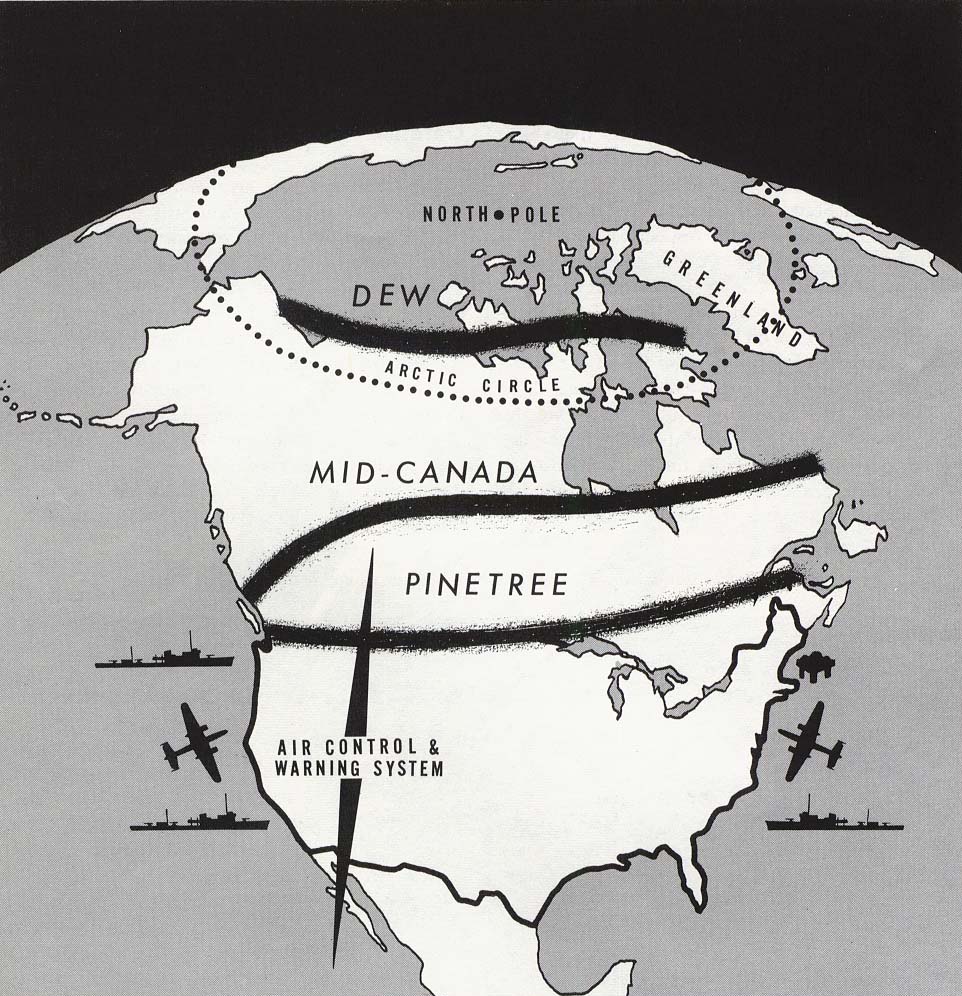

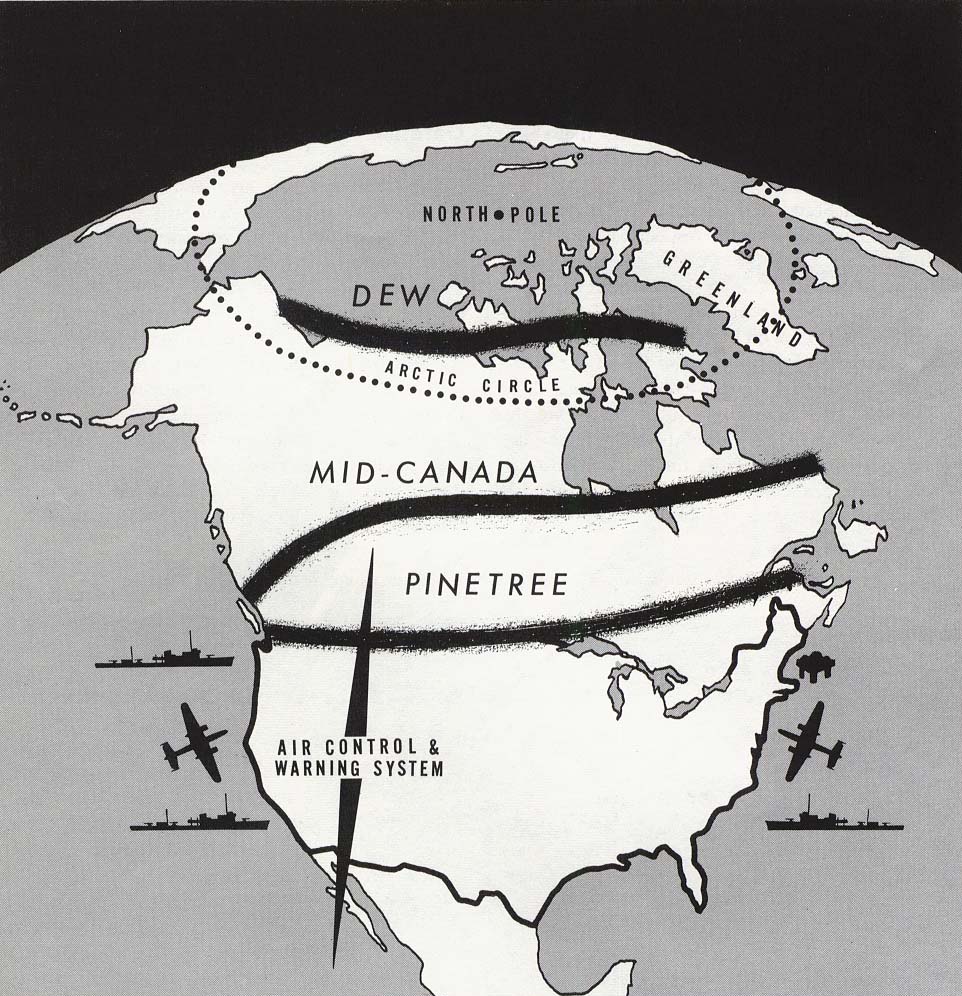

To defend

To defend North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere and almost entirely within the Western Hemisphere. It is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South America and th ...

against a possible enemy attack, Canada and the United States began to work very closely together in the 1950s. The North American Aerospace Defense Command

North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD ), known until March 1981 as the North American Air Defense Command, is a combined organization of the United States and Canada that provides aerospace warning, air sovereignty, and protection ...

(NORAD) created a joint air-defence system. In northern Canada

Northern Canada, colloquially the North or the Territories, is the vast northernmost region of Canada variously defined by geography and politics. Politically, the term refers to the three territories of Canada: Yukon, Northwest Territories an ...

, the Distant Early Warning Line

The Distant Early Warning Line, also known as the DEW Line or Early Warning Line, was a system of radar stations in the northern Arctic region of Canada, with additional stations along the north coast and Aleutian Islands of Alaska (see Proj ...

(or Dew Line) was established to give warning of Soviet bomber

A bomber is a military combat aircraft designed to attack ground and naval targets by dropping air-to-ground weaponry (such as bombs), launching torpedoes, or deploying air-launched cruise missiles. The first use of bombs dropped from an air ...

s heading over the north pole

The North Pole, also known as the Geographic North Pole or Terrestrial North Pole, is the point in the Northern Hemisphere where the Earth's axis of rotation meets its surface. It is called the True North Pole to distinguish from the Ma ...

. Similar early warning radar systems were also developed in the middle of Canada, known as the Mid-Canada Line

The Mid-Canada Line (MCL), also known as the McGill Fence, was a line of radar stations running east–west across the middle of Canada, used to provide early warning of a Soviet bomber attack on North America. It was built to supplement the ...

; and across the 50th parallel north

The 50th parallel north is a circle of latitude that is 50 degree (angle), degrees true north, north of the Earth, Earth's equator, equatorial plane. It crosses Europe, Asia, the Pacific Ocean, North America, and the Atlantic Ocean.

At this lati ...

, known as the Pinetree Line

The Pinetree Line was a series of radar stations located across the northern United States and southern Canada at about the 50th parallel north, along with a number of other stations located on the Atlantic and Pacific coasts. Run by North Ame ...

.

Domestic anti-Communism

Canada addressed the threat posed by Communist sympathizers in a manner more moderate than in the United States. The United States wished the Canadian government would go further, asking for a purge oftrade union

A trade union (labor union in American English), often simply referred to as a union, is an organization of workers intent on "maintaining or improving the conditions of their employment", ch. I such as attaining better wages and benefits ...

s, but the Canadian government left the purge of trade unions to the AFL–CIO

The American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL–CIO) is the largest federation of unions in the United States. It is made up of 56 national and international unions, together representing more than 12 million ac ...

. The American officials were especially concerned about the sailors on Great Lakes

The Great Lakes, also called the Great Lakes of North America, are a series of large interconnected freshwater lakes in the mid-east region of North America that connect to the Atlantic Ocean via the Saint Lawrence River. There are five lakes ...

freight vessels, and, in 1951, Canada added them to those already screened by its secret anti-communist screening program. The Communist Party of Canada

The Communist Party of Canada (french: Parti communiste du Canada) is a federal political party in Canada, founded in 1921 under conditions of illegality. Although it does not currently have any parliamentary representation, the party's can ...

had not been outlawed since Section 98

Section 98 (s. 98) of the ''Criminal Code'' of Canada was a law enacted after the Winnipeg general strike of 1919 banning "unlawful associations." It was used in the 1930s against the Communist Party of Canada.

After the Winnipeg general strike ...

, which was repealed by Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King

William Lyon Mackenzie King (December 17, 1874 – July 22, 1950) was a Canadian statesman and politician who served as the tenth prime minister of Canada for three non-consecutive terms from 1921 to 1926, 1926 to 1930, and 1935 to 1948. A L ...

in 1935.

Despite its comparatively moderate stance towards Communism, the Canadian state continued intensive surveillance of Communists and sharing of intelligence with the United States. PROFUNC was a Government of Canada

The government of Canada (french: gouvernement du Canada) is the body responsible for the federal administration of Canada. A constitutional monarchy, the Crown is the corporation sole, assuming distinct roles: the executive, as the ''Crown-i ...

top secret

Classified information is material that a government body deems to be sensitive information that must be protected. Access is restricted by law or regulation to particular groups of people with the necessary security clearance and need to kn ...

plan to identify and detain Communist

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, ...

sympathizers during the height of the Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because t ...

.

Tensions between Canada and the United States heightened during this time as on April 4, 1957, Canadian Ambassador to Egypt, E. Herbert Norman

Egerton Herbert Norman (September 1, 1909 – April 4, 1957) was a Canadian diplomat and historian. Born in Japan to missionary parents, he became an historian of modern Japan before joining the Canadian foreign service. His most influential bo ...

, leaped to his death from a Cairo

Cairo ( ; ar, القاهرة, al-Qāhirah, ) is the capital of Egypt and its largest city, home to 10 million people. It is also part of the largest urban agglomeration in Africa, the Arab world and the Middle East: The Greater Cairo metr ...

building after the United States Senate Subcommittee on Internal Security released a textual record of a previous hearing to the media. Despite having been cleared several years earlier—first by the RCMP

The Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP; french: Gendarmerie royale du Canada; french: GRC, label=none), commonly known in English as the Mounties (and colloquially in French as ) is the federal and national police service of Canada. As poli ...

in 1950, then again by the Canadian Minister of External Affairs, Lester B. Pearson (later Prime Minister)—the American media portrayed Norman as a spy and traitor. The only evidence the United States had was that as a student at Cambridge and Harvard he was a part of a Marxist communist study group. This made Pearson, who was still External Affairs Minister, backed by outrage across the country, send a note

Note, notes, or NOTE may refer to:

Music and entertainment

* Musical note, a pitched sound (or a symbol for a sound) in music

* ''Notes'' (album), a 1987 album by Paul Bley and Paul Motian

* ''Notes'', a common (yet unofficial) shortened version ...

to the U.S. Government, threatening to offer no more security information on Canadian citizens until it was guaranteed that this information would not slip beyond the executive branch of the government.

Peacekeeping

It was during the Cold War period that Canada began to assert the international clout that went along with the reputation it had built on the international stage in World War I and World War II. In theKorean War

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Korean War

, partof = the Cold War and the Korean conflict

, image = Korean War Montage 2.png

, image_size = 300px

, caption = Clockwise from top:{ ...

, the moderately sized contingent of volunteer soldiers from Canada made noteworthy contributions to the United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be a centre for harmoni ...

forces and served with distinction. Of particular note is the Princess Patricia's Canadian Light Infantry

Princess Patricia's Canadian Light Infantry (PPCLI, generally referred to as the Patricia's) is one of the three Regular Force infantry regiments of the Canadian Army of the Canadian Armed Forces. Formed in 1914, it is named for Princess Patrici ...

's contribution to the Battle of Kapyong

The Battle of Kapyong (or Gapyeong) ( ko, 가평전투, 22–25 April 1951), also known as the Battle of Jiaping (), was fought during the Korean War between United Nations Command (UN) forces—primarily Canadian, Australian, and New Zealand� ...

.

Canada's major Cold War contribution to international politics was made in the innovation and implementation of 'Peacekeeping

Peacekeeping comprises activities intended to create conditions that favour lasting peace. Research generally finds that peacekeeping reduces civilian and battlefield deaths, as well as reduces the risk of renewed warfare.

Within the United ...

'. Although a United Nations military force had been proposed and advocated for the preservation of peace vis a vis the U.N.'s mandate by Canada's representatives Prime Minister Mackenzie King and his Secretary of State for External Affairs Louis St. Laurent at the United Nations Conference on International Organization in San Francisco in June 1945, it was not adopted at that time.

During the

During the Suez Crisis

The Suez Crisis, or the Second Arab–Israeli war, also called the Tripartite Aggression ( ar, العدوان الثلاثي, Al-ʿUdwān aṯ-Ṯulāṯiyy) in the Arab world and the Sinai War in Israel,Also known as the Suez War or 1956 Wa ...

of 1956, the idea promoted by Canada in 1945 of a United Nations military force returned to the fore. The conflict involving Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* The United Kingdom, a sovereign state in Europe comprising the island of Great Britain, the north-eastern part of the island of Ireland and many smaller islands

* Great Britain, the largest island in the United King ...

, France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

, Israel

Israel (; he, יִשְׂרָאֵל, ; ar, إِسْرَائِيل, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, label=none, translit=Medīnat Yīsrāʾēl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

and Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning the North Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via a land bridg ...

quickly developed into a potential flashpoint between the emerging 'superpower

A superpower is a state with a dominant position characterized by its extensive ability to exert influence or project power on a global scale. This is done through the combined means of economic, military, technological, political and cultural ...

s' of the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

and the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

as the Soviets made intimations that they would militarily support Egypt's cause. The Soviets went as far as to say they would be willing to use "all types of modern weapons of destruction" on London and Paris—an overt threat of nuclear attack. Canadian diplomat Lester B. Pearson re-introduced then-Prime Minister Louis St. Laurent's UN military force concept in the form of an 'Emergency Force' that would intercede and divide the combatants, and form a buffer zone or 'human shield

A human shield is a non-combatant (or a group of non-combatants) who either volunteers or is forced to shield a legitimate military target in order to deter the enemy from attacking it. The use of human shields as a resistance measure was popula ...

' between the opposing forces. Pearson's United Nations Emergency Force

The United Nations Emergency Force (UNEF) was a military and peacekeeping operation established by the United Nations General Assembly to secure an end to the Suez Crisis of 1956 through the establishment of international peacekeepers on the bor ...

(UNEF), the first peacekeeping force, was deployed to separate the combatants, and enforce a ceasefire

A ceasefire (also known as a truce or armistice), also spelled cease fire (the antonym of 'open fire'), is a temporary stoppage of a war in which each side agrees with the other to suspend aggressive actions. Ceasefires may be between state ac ...

and resolution that was drawn up to end the hostilities.

Canada–U.S. tensions (1961–1980)

Diefenbaker and the Missile Crisis (1961–63)

Great debate broke out while John Diefenbaker wasPrime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is ...

as to whether Canada should accept U.S. nuclear weapons on its territory. Diefenbaker had already agreed to buy the BOMARC

The Boeing CIM-10 BOMARC (Boeing Michigan Aeronautical Research Center) (IM-99 Weapon System prior to September 1962) was a supersonic ramjet powered long-range surface-to-air missile (SAM) used during the Cold War for the air defense of North ...

missile system from the Americans, which would be not as effective without nuclear warheads, but balked at permitting the weapons into Canada.

Canada also maintained diplomatic and economic ties with Cuba following the

Canada also maintained diplomatic and economic ties with Cuba following the Cuban Revolution

The Cuban Revolution ( es, Revolución Cubana) was carried out after the 1952 Cuban coup d'état which placed Fulgencio Batista as head of state and the failed mass strike in opposition that followed. After failing to contest Batista in co ...

. Prior to the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis

The Cuban Missile Crisis, also known as the October Crisis (of 1962) ( es, Crisis de Octubre) in Cuba, the Caribbean Crisis () in Russia, or the Missile Scare, was a 35-day (16 October – 20 November 1962) confrontation between the United S ...

, the insistence on a much more placated policy towards the Cuban government had been a source of contention between the United States and Canada. Diefenbaker firmly stood by his policy decision, insisting that this was the result of the rights of states to establish their own forms of government, rejection of current US interpretation of the Monroe Doctrine

The Monroe Doctrine was a United States foreign policy position that opposed European colonialism in the Western Hemisphere. It held that any intervention in the political affairs of the Americas by foreign powers was a potentially hostile act ...

as well as Canada's right to establish its own foreign policy. Concern in the Canadian government was focused primarily on nuclear weapons, many politicians in the opposition and in power believed that as long as the US president retained absolute control of the nuclear weapons, Canadian forces could be ordered to undertake nuclear missions for the US without Canadian consent.

During the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962, Canada was expected to fall in line with American foreign policy, in that Canada's military forces were expected to go on immediate war alert status. Diefenbaker however, refused to do so emphasizing the need for United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be a centre for harmoni ...

intervention. It would only be after a tense phone call between President John F. Kennedy and Diefenbaker that Canada's armed forces would begin preparations for "immediate enemy attack."

Although the crisis would eventually be solved by diplomatic talks between Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev (– 11 September 1971) was the First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964 and chairman of the country's Council of Ministers from 1958 to 1964. During his rule, Khrushchev s ...

and Kennedy, nothing would loom larger over the Canadian state in the months following the crisis than the governing party's disarray on the question of nuclear arms.

Pearson and Trudeau (1963–84)

In the 1963 Canadian election, Diefenbaker was replaced by the famed diplomat Lester B. Pearson, who accepted the warheads. Further tensions developed when Pearson criticized the American role in theVietnam War

The Vietnam War (also known by #Names, other names) was a conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. It was the second of the Indochina Wars and was officially fought between North Vie ...

in a speech he gave at Temple University

Temple University (Temple or TU) is a public state-related research university in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. It was founded in 1884 by the Baptist minister Russell Conwell and his congregation Grace Baptist Church of Philadelphia then calle ...

in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Since ...

. (Also of note: In 1968, Canada's three separate armed services were unification into the Canadian Armed Forces.)

Shortly after the implementation of economic policies and tariffs in 1971, known as the Nixon shock, the Canadian government began to articulate a Third Option policy; with plans to diversify Canadian trade and to downgrade the importance of its relationship with the United States. In a 1972 speech in Ottawa, Nixon declared the "special relationship" between Canada and the United States dead.

During this period, Canada played a middle power

In international relations, a middle power is a sovereign state that is not a great power nor a superpower, but still has large or moderate influence and international recognition.

The concept of the "middle power" dates back to the origin ...

role in international affairs, and pursued diplomatic relations with Communist countries

A communist state, also known as a Marxist–Leninist state, is a one-party state that is administered and governed by a communist party guided by Marxism–Leninism. Marxism–Leninism was the state ideology of the Soviet Union, the Cominte ...

that the US had severed ties with, such as Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribb ...

and Red China after their respective revolutions. (The latter was not internationally recognized at the time.) Canada argued that rather than being soft on Communism, it was pursuing a strategy of "constructive engagement

Constructive engagement was the name given to the conciliatory foreign policy of the Reagan administration towards the apartheid regime in South Africa. Devised by Chester Crocker, Reagan's U.S. Assistant Secretary of State for African Affair ...

" whereby it sought to influence Communism through the course of its international relationships.

Canada also refused to join the Organization of American States

The Organization of American States (OAS; es, Organización de los Estados Americanos, pt, Organização dos Estados Americanos, french: Organisation des États américains; ''OEA'') is an international organization that was founded on 30 Apri ...

, disliking the support and tolerance of the Cold War OAS for dictators. Under Pearson's successor, Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau

Joseph Philippe Pierre Yves Elliott Trudeau ( , ; October 18, 1919 – September 28, 2000), also referred to by his initials PET, was a Canadian lawyer and politician who served as the 15th prime minister of Canada from 1968 to 1979 and ...

, U.S.-Canadian policies grew further apart. Trudeau removed nuclear weapons from Canadian soil, formally recognized the People's Republic of China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, most populous country, with a Population of China, population exceeding 1.4 billion, slig ...

, established a personal friendship with Cuban leader Fidel Castro

Fidel Alejandro Castro Ruz (; ; 13 August 1926 – 25 November 2016) was a Cuban revolutionary and politician who was the leader of Cuba from 1959 to 2008, serving as the prime minister of Cuba from 1959 to 1976 and president from 1976 to 20 ...

, and decreased the number of Canadian troops stationed at NATO bases in Europe.

In addition, Canada may have played a small role in helping to bring about ''glasnost

''Glasnost'' (; russian: link=no, гласность, ) has several general and specific meanings – a policy of maximum openness in the activities of state institutions and freedom of information, the inadmissibility of hushing up problems, ...

'' and ''perestroika

''Perestroika'' (; russian: links=no, перестройка, p=pʲɪrʲɪˈstrojkə, a=ru-perestroika.ogg) was a political movement for reform within the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) during the late 1980s widely associated wit ...

''. In the mid-1970s, Alexander Yakovlev

Alexander Nikolayevich Yakovlev (russian: Алекса́ндр Никола́евич Я́ковлев; 2 December 1923 – 18 October 2005) was a Soviet and Russian politician, diplomat, and historian. A member of the Politburo and Secreta ...

was appointed as ambassador to Canada, remaining at that post for a decade. During this time, he and Trudeau became close friends.

Final years of the Cold War (1980–1991)

Prime MinisterBrian Mulroney

Martin Brian Mulroney ( ; born March 20, 1939) is a Canadian lawyer, businessman, and politician who served as the 18th prime minister of Canada from 1984 to 1993.

Born in the eastern Quebec city of Baie-Comeau, Mulroney studied political s ...

and President Ronald Reagan

Ronald Wilson Reagan ( ; February 6, 1911June 5, 2004) was an American politician, actor, and union leader who served as the 40th president of the United States from 1981 to 1989. He also served as the 33rd governor of California from 1967 ...

had a close relationship, but the 1980s also saw widespread protests against American testing of cruise missile

A cruise missile is a guided missile used against terrestrial or naval targets that remains in the atmosphere and flies the major portion of its flight path at approximately constant speed. Cruise missiles are designed to deliver a large warh ...

s in Canada's north.

In the early 1980s, Yakovlev accompanied Mikhail Gorbachev

Mikhail Sergeyevich Gorbachev (2 March 1931 – 30 August 2022) was a Soviet politician who served as the 8th and final leader of the Soviet Union from 1985 to the country's dissolution in 1991. He served as General Secretary of the Com ...

, who at the time was the Soviet official in charge of agriculture

Agriculture or farming is the practice of cultivating plants and livestock. Agriculture was the key development in the rise of sedentary human civilization, whereby farming of domesticated species created food surpluses that enabled people ...

, on his tour of Canada. The purpose of the visit was to tour Canadian farms and agricultural institutions in the hopes of taking lessons that could be applied in the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

; however, the two began, tentatively at first, to discuss the need for liberalization in the Soviet Union. Yakovlev then returned to Moscow

Moscow ( , US chiefly ; rus, links=no, Москва, r=Moskva, p=mɐskˈva, a=Москва.ogg) is the capital and largest city of Russia. The city stands on the Moskva River in Central Russia, with a population estimated at 13.0 million ...

, and would eventually be called the "godfather of glasnost

''Glasnost'' (; russian: link=no, гласность, ) has several general and specific meanings – a policy of maximum openness in the activities of state institutions and freedom of information, the inadmissibility of hushing up problems, ...

," the intellectual force behind Gorbachev's reform program. In 1987, Canada released a long-awaited

In 1987, Canada released a long-awaited White Paper

A white paper is a report or guide that informs readers concisely about a complex issue and presents the issuing body's philosophy on the matter. It is meant to help readers understand an issue, solve a problem, or make a decision. A white paper ...

on Defence; signalling its intent to re-assert sovereignty over its Arctic waters. Concerned that Soviet submarines were operating in Canada's Arctic Archipelago

The Arctic Archipelago, also known as the Canadian Arctic Archipelago, is an archipelago lying to the north of the Canadian continental mainland, excluding Greenland (an autonomous territory of Denmark).

Situated in the northern extremity of No ...

, several programs were proposed to close the gap between Canada's current capabilities and its commitments to NATO. Project Spinnaker was born, a joint Canada–US endeavour whose secret purpose was to provide the capability to monitor submarine traffic in Canadian Arctic waters by deploying acoustic listening posts on the seafloor. This project required the development of a large autonomous underwater vehicle—named Theseus

Theseus (, ; grc-gre, Θησεύς ) was the mythical king and founder-hero of Athens. The myths surrounding Theseus his journeys, exploits, and friends have provided material for fiction throughout the ages.

Theseus is sometimes describ ...

—whose sole purpose was to lay communications trunk cables on the seafloor in waters with a permanent ice cover. In the spring of 1996, Theseus was transported to CFS Alert (on the northeastern tip of Ellesmere Island

Ellesmere Island ( iu, script=Latn, Umingmak Nuna, lit=land of muskoxen; french: île d'Ellesmere) is Canada's northernmost and third largest island, and the tenth largest in the world. It comprises an area of , slightly smaller than Great Br ...

) and then was deployed from an ice camp where it laid 180 km of fibre optic cable on the seafloor in ice-covered waters, successfully delivering it to an acoustic array deployed on the edge of the Continental Shelf

A continental shelf is a portion of a continent that is submerged under an area of relatively shallow water, known as a shelf sea. Much of these shelves were exposed by drops in sea level during glacial periods. The shelf surrounding an island ...

.

Post-Cold War

When the Cold War ended,Canadian Forces

}

The Canadian Armed Forces (CAF; french: Forces armées canadiennes, ''FAC'') are the unified military forces of Canada, including sea, land, and air elements referred to as the Royal Canadian Navy, Canadian Army, and Royal Canadian Air Force.

...

were withdrawn from their NATO commitments in Germany, military spending was cut, and air raid sirens were removed across the country. The Diefenbunkers, Canada's military-operated fallout shelters

A fallout shelter is an enclosed space specially designated to protect occupants from radioactive debris or fallout resulting from a nuclear explosion. Many such shelters were constructed as civil defense measures during the Cold War.

Duri ...

designed to ensure continuity of government

Continuity of government (COG) is the principle of establishing defined procedures that allow a government to continue its essential operations in case of a catastrophic event such as nuclear war.

COG was developed by the British government befo ...

, were decommissioned. In 1994, the last active United States military base in Canada, Naval Station Argentia

Naval Station Argentia is a former base of the United States Navy that operated from 1941 to 1994. It was established in the community of Argentia in what was then the Dominion of Newfoundland, which later became the tenth Canadian province, Ne ...

Newfoundland, was decommissioned and the facility was turned over to the Government of Canada

The government of Canada (french: gouvernement du Canada) is the body responsible for the federal administration of Canada. A constitutional monarchy, the Crown is the corporation sole, assuming distinct roles: the executive, as the ''Crown-i ...

. The base was a storage facility for the Mk 101 Lulu and B57 nuclear bombs and a key node in the US Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

's SOSUS

The Sound Surveillance System (SOSUS) was a submarine detection system based on passive sonar developed by the United States Navy to track Soviet Navy, Soviet submarines. The system's true nature was classified with the name and acronym SOSUS them ...

network to detect Soviet

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

nuclear submarine

A nuclear submarine is a submarine powered by a nuclear reactor, but not necessarily nuclear-armed. Nuclear submarines have considerable performance advantages over "conventional" (typically diesel-electric) submarines. Nuclear propulsion, ...

s. Canada continues to participate in Cold War institutions such as NORAD and NATO, but they have been given new missions and priorities.

The Cold War in Canada came to an end during the period of 1990–1995 as the traditional mission to contain Soviet expansion faded into the new realities of warfare. The Cold War required permanent foreign deployments to Western Europe, something which was no longer necessary, and as such bases closed down. Less equipment was needed, and so much was sold off, soon to be replaced by newer equipment designed for future conflicts. At home, bases were closed and operations consolidated and streamlined for maximum efficiency, as by the early 1990s many Canadians were openly questioning the necessity of large defence budgets.

In 1990, Canadian troops were deployed to assist provincial police in Québec in an effort to defuse tensions between Mohawk Warriors and the

The Cold War in Canada came to an end during the period of 1990–1995 as the traditional mission to contain Soviet expansion faded into the new realities of warfare. The Cold War required permanent foreign deployments to Western Europe, something which was no longer necessary, and as such bases closed down. Less equipment was needed, and so much was sold off, soon to be replaced by newer equipment designed for future conflicts. At home, bases were closed and operations consolidated and streamlined for maximum efficiency, as by the early 1990s many Canadians were openly questioning the necessity of large defence budgets.

In 1990, Canadian troops were deployed to assist provincial police in Québec in an effort to defuse tensions between Mohawk Warriors and the Sûreté du Québec

The (SQ; , ) is the provincial police service for the Canadian province of Quebec. No official English name exists, but the agency's name is sometimes translated to 'Quebec Provincial Police' or QPP in English-language sources. The headquarters ...

and local residents. In 1991 Canadian Forces personnel deployed in support of the American liberation of Kuwait. By 1992, Canadian peacekeepers were deployed to Cambodia, Croatia and Somalia. In 1993 Balkan involvement expanded into Bosnia and Canadian troops participated in some of the fiercest combat since the Korean War during Operation Medak Pocket

Operation Medak Pocket ( sh, script=Latn, Operacija Medački džep, ) was a military operation undertaken by the Croatian Army between 9 – 17 September 1993, in which a salient reaching the south suburbs of Gospić, in the south-central Lika ...

.

By the end of the 1990s, Canada would have a completely different military, one more inclined towards the rigours of peacekeeping and peace-making operations under multinational coalitions. The country would be further involved in the Yugoslav Wars

The Yugoslav Wars were a series of separate but related Naimark (2003), p. xvii. ethnic conflicts, wars of independence, and insurgencies that took place in the SFR Yugoslavia from 1991 to 2001. The conflicts both led up to and resulted from ...

throughout the rest of the decade, would become involved in Haiti, and would further see action again in Zaire and East Timor

East Timor (), also known as Timor-Leste (), officially the Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste, is an island country in Southeast Asia. It comprises the eastern half of the island of Timor, the exclave of Oecusse on the island's north-w ...

. The Navy, by decade's end (and prior to the modern post-9/11 era), was comparatively brand new, the Air Force well-balanced and modern as well. The Army began to acquire new equipment, such as the LAV-III, Bison APC and the Coyote Reconnaissance Vehicle

The LAV II Bison and Coyote are armoured cars (or armoured personnel carriers) built by General Dynamics Land Systems Canada for the Canadian Forces.

It is based on the Mowag Piranha 8x8.

Bison vehicles have also been used (to a lesser exten ...

as it transitioned to fighting irregular warfare instead of the large tank battles once feared would rage across Western Europe. It is with Canada's late-Cold War and early-Peacekeeping Era military that Canada would embark on its deployment to Afghanistan, currently Canada's longest-running war.

In recent years, Canada has been involved in tensions with Russia following the takeover of Crimea from Ukraine and China due to its diplomatic spat over various issues such as treatment of Uyghurs, Meng Wenzhou and Hong Kong protests.

See also

*ABCANZ Armies

ABCANZ Armies (formally, the American, British, Canadian, Australian and New Zealand Armies' Program) is a program aimed at optimizing interoperability and standardization of training and equipment between the armies of Australia, Canada, New Z ...

* Structure of the Canadian Armed Forces in 1989

*'' On Guard For Thee'' (1981) — a 3-part CBC/ NFB documentary series about Canada's national security operations during the Cold-War era, including the Gouzenko Affair and the 1970 October Crisis.

Notes

References

Bibliography

* * * *Further reading

* Balawyder, Aloysius. 2000. ''In the Clutches of the Kremlin: Canadian-East European Relations, 1945-1962.''Columbia University Press

Columbia University Press is a university press based in New York City, and affiliated with Columbia University. It is currently directed by Jennifer Crewe (2014–present) and publishes titles in the humanities and sciences, including the fie ...

. 192 pp.

* Barry, Farrell R. 1969. ''The Making of Canadian Foreign Policy.'' Scarborough: Prentice-Hall.

*Belshaw, John Douglas. 2018.Cold War Canada, 1945-1991

" Ch. 9 in ''Canadian History: Post-Confederation''. BC Open Textbook Project. *Cavell, Richard, ed. 2004. ''Love, Hate, and Fear in Canada's Cold War''. University of Toronto Press. 216 pp. * Adam Chapnick. 2005. ''The Middle Power Project: Canada and the Founding of the United Nations'' University of British Columbia Press. . * Clark-Jones, Melissa. 1987. ''A Staple State: Canadian Industrial Resources in Cold War.'' U. of Toronto Press. 260 pp. * Clearwater, John. 1998.

Canadian nuclear weapons: the untold story of Canada's Cold War arsenal

'. Dundurn Press. * Cuff, R. D. and J. L. Granatstein. 1975. ''Canadian-American Relations in Wartime: From the Great War to the Cold War.'' Toronto: Hakkert. 205 pp. * David, Dewitt, and John Kirton. 1983. ''Canada as a Principal Power.'' Toronto: John Wiley. * Donaghy, Greg, ed. 1998. ''Canada and the Early Cold War, 1943–1957.'' Ottawa: Dept. of Foreign Affairs and International Trade. 255 pp. * Eayrs, James. 1972. ''In Defence of Canada. III: Peacemaking and Deterrence.'' U. of Toronto Press. 448 pp. * Granatstein, J. L., and David Stafford. 1991. ''Spy Wars: Espionage and Canada from Gouzenko to Glasnost''. . * Herd, Alex. 2006 February 6.

Canada and the Cold War

" ''The Canadian Encyclopedia'' (last edited 2021 March 6). *Holmes, John W. 1979, 1982. ''The Shaping of Peace: Canada and the Search for World Order, 1943–1957,'' 2 vols. University of Toronto Press. * Hristov, Alen. 2018 December 8.

The Gouzenko Affair and the Development of Canadian Intelligence

" ''

E-International Relations

''E-International Relations'' (''E-IR'') is an open-access website covering international relations and international politics. It provides an academic perspective on global events. Its editor-in-chief iStephen McGlinchey The website has published ...

''.

* Knight, Amy. 2005. ''How The Cold War Began''.

* Maloney, Sean M. 2002. ''Canada and UN Peacekeeping: Cold War by Other Means.'' St. Catharines, ON: Vanwell. 265 pp.

* Matthews, Robert O., and Cranford Pratt, eds. 1988. ''Human Rights in Canadian Foreign Policy.'' McGill–Queen's University Press.

* McShane, Brendan. 2021 February 21.It's War. It's War. It's Russia

" ''

Canada's History

''Canada's History'' () is the official magazine of Canada's National History Society. It is published six times a year and aims to foster greater popular interest in Canadian history.

Founded as ''The Beaver'' in 1920 by the Hudson's Bay Com ...

''. Canada's National History Society

Canada's National History Society is a charitable organization based in Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada. The Society was founded in 1994 by the Hudson's Bay Company (HBC) for the purpose of promoting greater popular interest in Canadian history princip ...

.

* Nossal, Kim Richard. 1989. ''The Politics of Canadian Foreign Policy'' (2nd ed.). Prentice-Hall.

* Oliver, Dean F. n.d.Canada and NATO

" Dispatches: Backgrounders in Canadian Military History. ''

Canadian War Museum

The Canadian War Museum (french: link=no, Musée canadien de la guerre; CWM) is a national museum on the country's military history in Ottawa, Ontario, Canada. The museum serves as both an educational facility on Canadian military history, in ad ...

''.

* Reid, Escott. 1977. ''Time of Fear and Hope: The Making of the North Atlantic Treaty, 1947–1949.'' McClelland and Stewart.

* Sharnik, John. 1987. ''Inside the Cold War: An Oral History''. .

* Smith, Denis. 1988. ''Diplomacy of Fear: Canada and the Cold War, 1941–1948.'' University of Toronto Press. 259 pp.

* Stephenson, Michael. 1983.The DEW Line

" '' The Beaver'' (Winter 1983):14-19. *Tucker Michael. 1980. ''Canadian Foreign Policy: Contemporary Issues and Themes.''

McGraw-Hill Ryerson

Ryerson Press was a Canadian book publishing company, active from 1919 to 1970.Janet B. Friskney"The Birth of The Ryerson Press Imprint" Historical Perspectives on Canadian Publishing. First established by the Methodist Book Room, a division of t ...

.

*Whitaker, Reg. c. 1984-1987. "Spy Scandal." ''Horizon Canada'' 10. Brampton, ON: Centre for the Study of Teaching Canada.

* Whitaker, Reg, and Gary Marcuse. 1994. ''Cold War Canada: The Making of a National Insecurity State, 1945–1957''. . 511 pp.

* Whitaker, Reg, and Steve Hewitt. 2003. ''Canada and the Cold War.'' Toronto: Lorimer. 256 pp.

*

*Cold War Culture: The Nuclear Fear of the 1950s and 1960s

" ''CBC Digital Archives''.

External links

– '' Canada: A People's History'', CBC Learning

Project Rustic: Journey to the Diefenbunker

– Diefenbunker Canada’s Cold War Museum, Canadian Heritage

Archived

*"Gouzenko: The Series" (podcast) – ''

Canada's History

''Canada's History'' () is the official magazine of Canada's National History Society. It is published six times a year and aims to foster greater popular interest in Canadian history.

Founded as ''The Beaver'' in 1920 by the Hudson's Bay Com ...

'', Canada's National History Society

Canada's National History Society is a charitable organization based in Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada. The Society was founded in 1994 by the Hudson's Bay Company (HBC) for the purpose of promoting greater popular interest in Canadian history princip ...

*Gouzenko Deciphered

(2020 September 8), interview with Evy Wilson, daughter of Igor Gouzenko *

Gouzenko Deciphered Part 2

(2020 October 7), interview with Calder Walton *

Gouzenko Deciphered Part 3

(2020 October 21), interview with Andrew Kavchak

Cold War Tech and Its Discontents

(2021 January 26) – ''Canada's History'', Canada's National History Society {{DEFAULTSORT:Canada in the Cold War

Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because t ...

Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because t ...

Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because t ...

Canada in the Cold War

Canada in the Cold War

Political history of Canada

Cold War history by country

Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because t ...

Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because t ...